In most modern versions of “Goldilocks and the Three Bears,” Goldilocks is depicted as a blonde-haired girl who trespasses in the home of three bears. She eats from three bowls of porridge and lays on three beds—with the last one being “just right” in each case (a concept now known as the Goldilocks Principle)—before being discovered by the bear family and escaping without incident.

These elements may seem like staples of the story, but none of them were actually present in the first written versions of the fairy tale. Read on to find out how “Goldilocks and the Three Bears” has evolved over the years.

Hungry as a Bear

In 1831, Eleanor Mure created a handmade book titled “The Story of The Three Bears” as a birthday present for her 4-year-old nephew [PDF]. She described it as a “celebrated nursery tale,” indicating its popularity in the oral tradition. But instead of a curious young girl, the intruder is an angry old woman; instead of eating porridge, she drinks milk. There’s also no mention of the bears being a nuclear family, although one of them is described as “little bear.” The ending is considerably darker than the modern version, with the bears trying—and failing—to burn and drown the woman before deciding to “chuck her aloft on St. Paul’s churchyard steeple.”

Six years later, Robert Southey published a similar tale in The Doctor, Vol. IV. The main character is still an old woman, but it’s porridge she eats, with the third bowl being “neither too hot, nor too cold, but just right.” All three bears are male and they’re given their now-common descriptions of small, medium, and large—which is reflected in the different typefaces used for their speech. The story finishes with the woman escaping by jumping out of a window, but her fate thereafter is a mystery.

Southey’s telling of the ursine tale proved so popular that not long afterwards George Nicol retold it in rhyming verse along with illustrations. Unaware of Mure’s earlier picture book (as it hadn’t been publicly published), Nicol describes Southey as the story’s “Great, original Concoctor.” Mure’s earlier authorship wasn’t widely known until the mid-20th century.

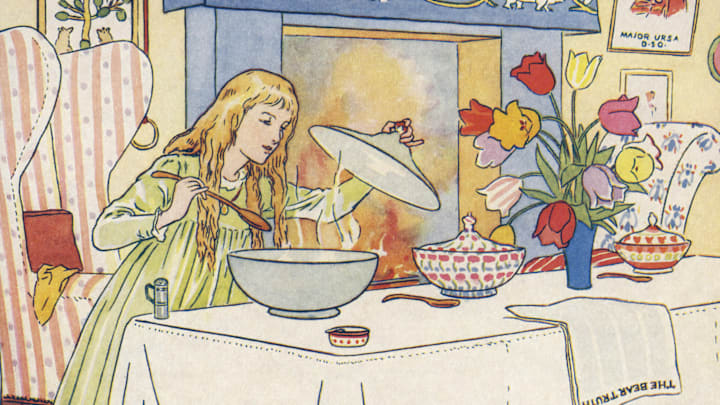

The fairy tale’s main character was then given an age reduction and a name in 1850. In A Treasury of Pleasure Books for Young Children, Joseph Cundall explains that he decided to make her a young girl “because there are so many other stories of old women.” However, she wasn’t yet known as Goldilocks, with Cundall naming her “Silver-hair.” By the end of this decade, the trio of bears had also become a father, mother, and child.

The girl’s hair started changing from silver to gold during the 1860s. In an 1864 literacy lesson book, for instance, she is called “Golden Hair.” The first known use of the name Goldilocks in connection with the tale comes from a letter published in 1875: “I was the little, small wee bear, and baby was to be the goldilocks.” However, the lack of capitalization suggests this may simply be a description of the character—goldilocks has been used to describe blonde hair since the 1540s—rather than a name. By at least 1904 she had officially been dubbed Goldilocks, but the name really caught on thanks to the popularity of Flora Annie Steel’s English Fairy Tales (1918).

Poking the Bear

Although the book that Eleanor Mure handmade is currently the oldest known definitive version of “Goldilocks and the Three Bears,” there are a few older stories that likely had an influence on the fairy tale.

Folklorist Joseph Jacobs believes the story may be predated by “Scrapefoot,” which is the same narrative, except that the trio of bears live in a castle and the intruder is a male fox named Scrapefoot. In his 1894 collection of fairy tales, Jacobs notes that “Scrapefoot” comes from “Mrs. H., who heard it from her mother over forty years ago.” The book’s publisher, David Nutt, theorizes that “Southey heard the story told of an old vixen, and mistook the rustic name of a female fox for the metaphorical application to women of fox-like temper.”

Which version of the story was told first isn’t known, but traces of the tale also appear in a few other older fairy tales. In 1812, the Brothers Grimm published “Snow White,” which sees the titular princess go into the home of the seven dwarfs, eat a little from each of their plates, and then fall asleep after testing each of their beds. When the dwarfs return home, they question who has been in their house—much like the three bears—but instead of being kicked out like Goldilocks, Snow White is invited to stay.

A passing resemblance to “Goldilocks and the Three Bears” can also be found in the Norwegian folktale “The Knights in Bear-shapes” and the Romanian story “The Bewitched Brothers.” The latter features two eagles rather than three bears, but both include a scene of a young woman stealing food after entering a house belonging to talking animals.

Read More About Fairy Tales: